Tigerland (2000)

written by: Ross Klavan and Michael McGruther

starring: Colin Farrell, Matthew Davis, Shea Whigham, Clifton Collins Jr.

Every major filmmaker eventually makes a war movie-- some make more than one, some work with a lesser known war, or a less examined facet. But eventually, Speilberg made Saving Private Ryan, Ang Lee made Ride with the Devil, John Huston made The Red Badge of Courage. These films reflect their directors, and Joel Schumacher's foray into the war film is no exception. His war movie is deeply specific to his perspective, and what more could we possibly expect or want? Tigerland presents a perspective that's not uniquely Schumacher, but it is the only perspective Schumacher could have. It's an intensely personal vision of brutality and the wearing down of individuals. Other directors have and will make movies about the war at home and the personal consequence of battle, but the interest in the singular person is very Schumacher. Working on a shoestring budget, with relative unknowns, and filming in under a month, he made a war movie that's intensely about the souls of specific young men. It struck me as a very personal, tender film about the cost and consequence of violent action, and that's a moving narrative as well as a continually worthwhile theme.

The old Truffaut line about how there are no truly anti-war films because, inevitably, war looks really dang cool on the big screen, is nearly successfully undercut here. That's quite an achievement, and I think it happens mainly because we're not seeing the war itself. Tigerland plays as anti-war because it shows the painful consequence of the very mentality that war requires without ever having an action sequence, or even a heroic moment of physicality. Set in 1971, Tigerland is a Vietnam movie, set entirely in basic training for a war that's getting worse and worse. You never see the war itself, or see anyone who feels that war is dang cool, and so the effect of movie-heroism is diminished.

This is not a showy movie, or a fancy movie. It's small and straight-forward. I found it somewhat striking in it's simplicity and affection. Our heroes are young men preparing to head off to war, and Schumacher feels deep tenderness for each of them which palpably bleeds into the film itself.

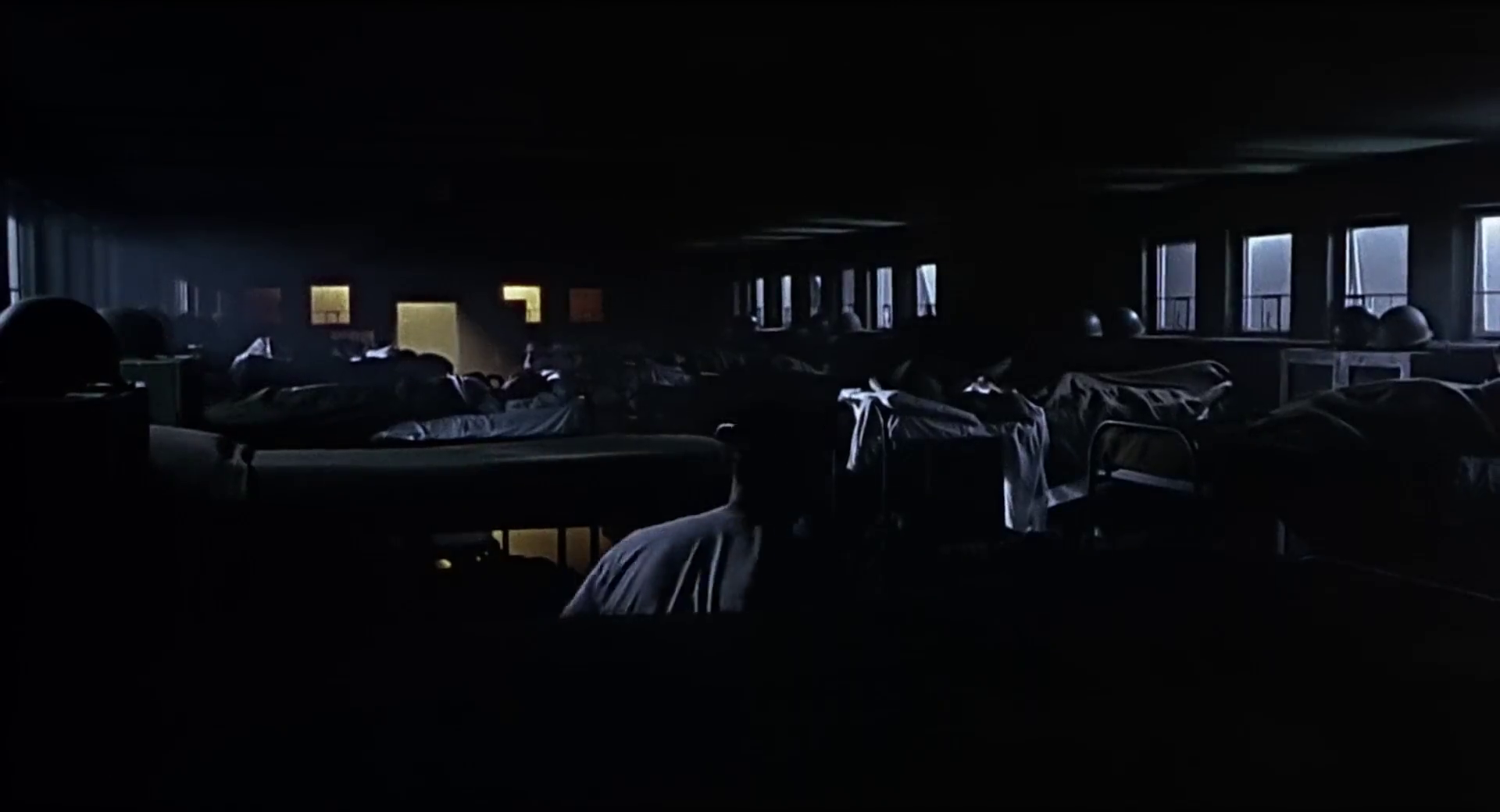

Coming off the occasional dips into handheld camerawork in Flawless, Schumacher actively commits to it here, creating a film that moves and rattles. He shot on 16mm, and that grainy, gritty quality gives many sequences in the movie a sense of aesthetic realism. I've seen enough newsreel footage from the late 60s and early 70s to have been impressed by how well Schumacher captures the qualities of those films. Tigerland has a warm and hazy glow over it and just enough shake to feel genuinely authentic. Any shot that doesn't include a recognizable, modern actor could be snipped out of a film of the era, and that's really something.

But it's the actors we're here for, and their characters are entirely who the movie is here for. Schumacher has put together a striking cast-- Colin Farrell in his first major American movie, Matthew Davis (ol' Warner from Legally Blonde himself), Shea Whigham, Clifton Collins Jr., all of whom deliver wonderful, intricate work. Even Michael Shannon shows up for a single scene. Schumacher, always a good sense of talent, has put together an impressive ensemble and uses them very well.

The brightest star is Colin Farrell, of course, who leads the film as Bozz, a young free-thinker, uninterested in war and unwilling to be broken down by the system he's been drafted into. He's rebellious, but a natural leader. People come to him for help, and he can't help but do his best for them. He's too sensitive and gentle to be a good soldier-- or at least to be the kind of good soldier (obedient, unquestioning, brutal) that his commanding officers want him to be, and think he needs to be to survive overseas. All of this works because Colin Farrell can carry it in his eyes. Whether delivering a playful twinkle or a tragic waver, Farrell is magnetic and striking. Each moment from him plays authentically and hits well. This is a very early film in his career, and already he's giving the kind of emotionally nuanced, trembling, raw-wound performance that he excels at now. He can't always hold the West Texas accent, but it doesn't matter much when you're caught in the way his voice shakes. I would even argue that his inconsistent accent gives his character, already sortof a wild fey child, an ethereal and unreal quality.

Farrell is one of our truly great actors, and in many ways, he is a gift that Joel Schumacher gave to us. Tigerland is the first of three collaborations between Schumacher and Farrell, and they work well together. It's clear why Farrell popped after this one. Schumacher clearly understands what makes Farrell such an engaging actor-- his big, dark eyes, his delicate bone structure, the way he carries pain in the fluttering muscle of his cheek. Though he may be capable of action and epic, Farrell soars in close up and when on the verge of tears and Schumacher knows it, taking full advantage of his beautiful, expressive face as often as possible. Rightly, Schumacher loves him and loves looking at him, and it helps create a character that we can engage with just as lovingly.

This is not at all to discount the rest of the cast, who are delivering perfectly what's required of them. Not everyone can shine like Colin Farrell, but not everyone should. In the way that you can see why people are drawn to Bozz, you can also see why Bozz is somewhat drawn to Jim Paxton (Davis). Paxton is hearty and solid, without any of the fluttering worry that weighs on Bozz. He's a good kid, one who wants to go to war to have the experience but also because he thinks it's the right thing to do. He's a young man who has dropped out of college to enlist, because he thinks deferment for education is unfair. It's noble, but stupid in 1971 when the war in Vietnam is deteriorating, and your chance of coming home is getting thinner and thinner. That nobility is what makes him appealing though, and I personally admire it. Bozz and Paxton talk throughout the film about what it would mean to go overseas, and what it would mean to not have to. "I'm here because there’s a place for me, and if I don’t go, someone has to take my place," Paxton says. "And if they die, they died for me.” That sentiment lingers, and it's that sentiment that becomes the backbone of the movie and of Bozz's character arc.

The rest of their platoon is a somewhat rag-tag collection of boys-- some of whom will make successful soldiers and some who won't. There are boys who don’t belong there, boys who can’t hack it, boys who want to be there too much. But they are all there, training to go to war, and if any one of them leaves, someone will have to take their place. Bozz's great plan at the start of the movie is to find a way to get himself kicked out of the army-- as the story progresses, the plan grows to include, ideally, getting everyone else sent home too. He's good at loopholes, and the kindness of his heart means that he finds them as often as possible for whoever he can, increasingly diminishing his own chance of getting out. Early on, he meets a young soldier with a wife and two small children at home. He guides this man through what to say to his commanding officers to be sent back to his family. Later, after a shattering experience in training, one of his platoon-mates threatens to desert. Sympathetic, Bozz guides him through an alternate option: make an argument of mental illness and don't run against the law. It's a way out Bozz might have been able to use for himself eventually, but doesn't get the chance.

The real shit-heel of their platoon is Wilson (Shea Whigham in a classic Shea Whigham role), a young man who wants to be there too badly. He's a psychopath with an ego, given permission and leeway to be cruel and to kill. He's unstable, but the army has room for unstable and can't necessarily afford to lose him. Early on, Bozz makes an offhanded joke that he won't be happy until he gets Wilson discharged, and there's a glimmer of truth under the jibe. You get the sense that, increasingly, if Bozz could get everyone sent home, so he was the only man left in the army, that would an acceptable trade for him. He doesn't want to die, but more than that, he doesn't want anyone else to die.

That kind of gentle softness towards your fellow man, even when your fellow man is trying to kill you, speaks to the particular perspective of this movie, and what I liked about it so much. It's not a particularly high stakes film in the concrete (eventually these boys will have to go to war and will likely die? Yes, we know) but in the abstract the stakes are that these young men-- each of them vibrant, unique, full of life and energy and hope and love-- will be ground down into grunts who kill, and that's all. The stakes are small, personal but vital. It's what Bozz is most afraid of. War can break you, cruelty can break you. To be broken down, not alive in the way that counts? That's the horror of this story. It's what Bozz is fighting against at every moment. He's a born leader and he could be a great soldier, but if being a soldier means destroying the parts of himself that are sensitive and gentle, then he won't do it. He values his emotional vulnerability.

I think that's pretty beautiful, and Schumacher frames it and presents it subtly and gently. Bozz's example and friendship, such as it is, changes the lives of everyone in his platoon. He reminds them, over and over, that they are people. They are men with souls. Their commanding officers are training them to survive at any cost, and have lost sight of them as individuals in the process. This idea congeals in Miter (Clifton Collins Jr.). Miter is given a position of authority over his fellow soldiers and deeply struggles with how to enforce or engage with that power. He isn't suited to it, because he's not a hard person and cannot rise to the hardness that he sees is expected of a man in his position. A lot of war movies play with the idea that war makes it very easy to be hard and callous (consider the scene in Saving Private Ryan where our heroes sift through the dog tags of hundreds of dead soldiers, thoughtless of the real lives behind each one of them). Tigerland seems to say that it's actually not that easy to harden up. It would be nice if it were easy, but it's not. Miter tries to be hard, tries to be the kind of tough, hard man that he sees is expected. But he's not that person, not mean-spirited, not callous. Forced into a sphere that requires hardness, it is the attempt to be hard that eventually breaks him. Soldiering, though he wants to do it, isn't for him. That hardening up, Tigerland convincingly states, is as much a cost of war as the physical loss of life.

Is it worth it? What kind of person thrives in that environment? Tigerland argues that no one thrives. Even Wilson, who wants most to be there and to do what the army wants him to do, isn't stable enough to handle it and remain functional. I felt some pity for him, and to produce pity for a mostly despicable character, who tries again and again to sabotage and kill our kind main characters-- that's a truly open-hearted piece of filmmaking.

It's also Schumacher's greatest strength. I've said it before, and more and more I believe it to be true. He has softness in his heart for everyone, and that translates into how he frames characters and shoots scenes. The way he shoots people is with love and generosity, always. Characters we should hate are given moments of sympathy. Characters we like are given ugly moments. Always, Schumacher sees his characters as multi-faceted people deserving of our attention. He goes out of his way to show you that-- to show Bozz's trembling face, his determination and his cowardice, Paxton's fear and fortitude, Wilson's pride and shame, all intermingled. It's also evidenced in the way his movies consistently feature lingering shots of extras and crowds. He wants us to look at faces and see people.

Paxton and Bozz start up a friendship on a nights leave where they end up spending the night together with a couple of local girls. This scene is vibrant and neon, a last thrill before the movie (and these boys lives) delve into the muddy drudgery of war. Occasionally the colors come back to pop-- vibrant greenery or the red splash of blood, but mostly it is gray, beige, and washed out. The world is as ground down by war and protocol just like our young men. It's a neat bit of work, and bit Schumacher. He's built a world of color and vibrancy, which he then visually breaks down, so the final sequences of the movie are nearly sepia toned. Impressive stuff.

In the end, during a shit-show of a training exercise gone wrong, Bozz discharges his weapon in Paxton's face, injuring him just badly enough to get him sent home. He won't own up to having done it on purpose, but it's clear he did. Paxton is a good man who shouldn't have to die overseas. So Bozz ensures that he won't. The final moment between them is so small, so intimate-- it's Schumacher at his best. The warmth he draws between these two actors is devastating. When the moment ends, and Bozz goes off ostensibly to die in Paxton's place, it's painful. But neither one of them is a broken person. They have been able to maintain their softness and humanity, and that, one feels, is a victory.

Tigerland is probably most interesting as a point of comparison against the bombastic, massive scale and size of a Batman & Robin. Tigerland is a purposefully smaller movie, and that tight, constrained quality in ways allows for more freedom. 16mm relieves some of the pressure of carrying a large 35mm camera around, lighting for it, setting up shots. The low budget of this picture means less studio interference, and I get the sense that the edges of this movie would be sanded down in a studio picture with a bigger investment on the line. The rawness of the film is inherently tied to how small it is, and that rawness is what makes the movie work. With a little more sheen on the surface, Tigerland would fail. Any tidier or shinier, and the movie would land false. So I applaud it's minor status, as a movie, as a form, as a Schumacher joint.

Overall: ★ ★ ★

Schumacherness: ★ ★

Up next: Bad Company (2002)